Effectiveness and Usefulness of Bone Turnover Marker in Osteoporosis Patients: A Multicenter Study in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background

This study aimed to investigate real-world data of C-terminal telopeptide (CTX), propeptide of type I collagen (P1NP), and osteocalcin through present multicenter clinical study, and retrospectively analyze the usefulness of bone turnover markers (BTMs) in Koreans.

Methods

The study focused on pre- and post-menopausal patients diagnosed with osteoporosis and excluded patients without certain test results or with test intervals of over 1 year. The demographic data and 3 BTMs (CTX, P1NP, and osteocalcin) were collected. The patients were classified by demographic characteristics and the BTM concentrations were analyzed by the group.

Results

Among women with no history of fractures, the levels of P1NP (N=2,100) were 43.544±36.902, CTX (N=1,855) were 0.373 ±0.927, and osteocalcin (N=219) were 10.81 ±20.631. Among men with no history of fractures, the levels of P1NP (N=221) were 48.498±52.892, CTX (N=201) were 0.370±0.351, and osteocalcin (N=15) were 7.868 ±10.674. Treatment with teriparatide increased the P1NP levels after 3 months in both men and women, with a 50% increase observed in women. Similarly, treatment with denosumab decreased the CTX levels after 3 months in both men and women, with a reduction of 50% observed in women.

Conclusions

The results of this study can contribute to the accurate assessment of bone replacement status in Koreans. We also provide the P1NP level in the Korean population for future comparative studies with other populations.

INTRODUCTION

International osteoporosis foundations and organizations, such as the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC), recommend the use of automated biochemical bone turnover markers (BTM), propeptide of type I collagen (P1NP) and C-terminal telopeptide (CTX), for post-treatment monitoring of patients with osteoporosis to determine the effectiveness of treatment.[1] BTM represents the ongoing process of bone turnover in the skeleton, where old bone is removed by resorption and new bone is created by osteogenesis. BTM reflects the rate of bone turnover and is the only non-invasive way to assess bone quality. Whereas bone density is a static indicator of bone metabolism, BTM is dynamic.[2]

However, in terms of practical application and usefulness in clinical practice, there are limitations in standardized data for Korean reference intervals according to the concentration of bone markers (P1NP, CTX) and disease-specific reference data for Korean patients in monitoring. Since 2014, automated protocols for both P1NP and CTX testing have been recommended by international societies and organizations, and reference values for automated testing methods have been studied in Korea.[3,4] Particularly, age- and gender-specific studies of these reference values have been conducted in Korea, and with the recent reimbursement of P1NP, related testing is being conducted in many hospitals in Korea.[5] However, many factors such as individual disease, medication history, and testing protocols are involved in the application of reference values in healthy individuals without osteoporosis to patients with osteoporosis.[4] Therefore, there are no standards for the monitoring of patients and prediction of fractures using bone markers in clinical practice.

The purpose of this study is to investigate real-world data of CTX, P1NP, and osteocalcin through the present multicenter clinical study, and retrospectively analyze the usefulness of BTM in Koreans. The observed data values would provide information that can be used as reference values for the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in patients.

METHODS

1. Subjects

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board of Chung-Ang University Hospital, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Yonsei University Health System, Kyung Hee University Healthcare System, Pusan National University Hospital, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, and Inha University Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from participants. The selection criteria were all pre- and post-menopausal patients undergoing osteoporosis screening. Criteria for osteoporosis were T-scores less than −2.5 according to the World Health Organization study group.[6] The exclusion criteria were patients with no CTX, P1NP, and osteocalcin test results before drug prescription, no secondary monitoring results, and test intervals of more than 1 year. The collected data included age, gender, menopause, fracture history, drug history, osteoporosis treatment history, CTX, P1NP, and osteocalcin.

The patients who were monitored with multicenter BTMs from January 1, 2015 were classified according to demographic characteristics (age, gender, menopause, drug history). The concentrations of BTMs by group were identified, and the values of each patient group were retrospectively analyzed.

2. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 4.3.1; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS software (version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistical analysis of mean, standard deviation, and median were performed for CTX, P1NP, and osteocalcin by gender, age, and fracture status. The association between BTM was analyzed by gender, age, menopausal status, osteoporosis status, and fracture status as confounding variables.

RESULTS

For women who have never had a fracture or osteoporosis, the levels of P1NP, CTX, and osteocalcin were measured. P1NP was 43.544±36.902 (N=2,100), CTX was 0.373±0.927 (N=1,855), and osteocalcin was 10.81±20.631 (N=219). For men without a fracture or osteoporosis history, P1NP was 48.498±52.892 (N=221), CTX was 0.370±0.351 (N= 201), and osteocalcin was 7.868±10.674 (N=15) (Table 1).

Bone turnover marker (P1NP, C-telopeptide, and osteocalcin) in subjects without fracture history (average age 70 years)

In women without fracture and osteoporosis history, P1NP (N=410) was 45.024±48.099, CTX (N=291) was 0.339±0.843, and osteocalcin (N=26) was 13.36±53.408. In men without fracture and osteoporosis history, P1NP (N=43) was 54.971±98.508, CTX (N=32) was 0.405±0.499, and osteocalcin (N=1) was 13.6 (Table 2).

Bone turnover marker (P1NP, C-telopeptide, and osteocalcin) in subjects without fracture history and osteoporosis (average age 70 years)

For women who are 50 years of age or older and have no history of osteoporosis drug use, P1NP (N=450) was 61.567 ±58.583, CTX (N=437) was 0.468±0.298, and osteocalcin (N=46) was 25.345±39.790 (Table 3).

Among women aged 50 years or older who had normal bone density and did not use osteoporosis drugs, P1NP (N= 206) was 71.472±79.762, CTX (N=193) was 0.476±0.317, and osteocalcin (N=29) was 29.744±49.406. In addition, P1NP (N=244) was 53.204±28.651, CTX (N=244) was 0.462±0.283, and osteocalcin (N=17) was 17.841±9.287 among women who are 50 years of age or older and have osteoporosis but no history of osteoporosis medication use (Table 4).

In the case of BTM (P1NP and CTX) levels according to the presence or absence of osteoporosis, the P1NP of osteoporosis participants (N=291) was 65.768±94.373 and CTX was 0.528±1.206. In addition, the P1NP of normal participants (N=472) was 48.026±49.364, and CTX was 0.361 ±0.673 (Table 5).

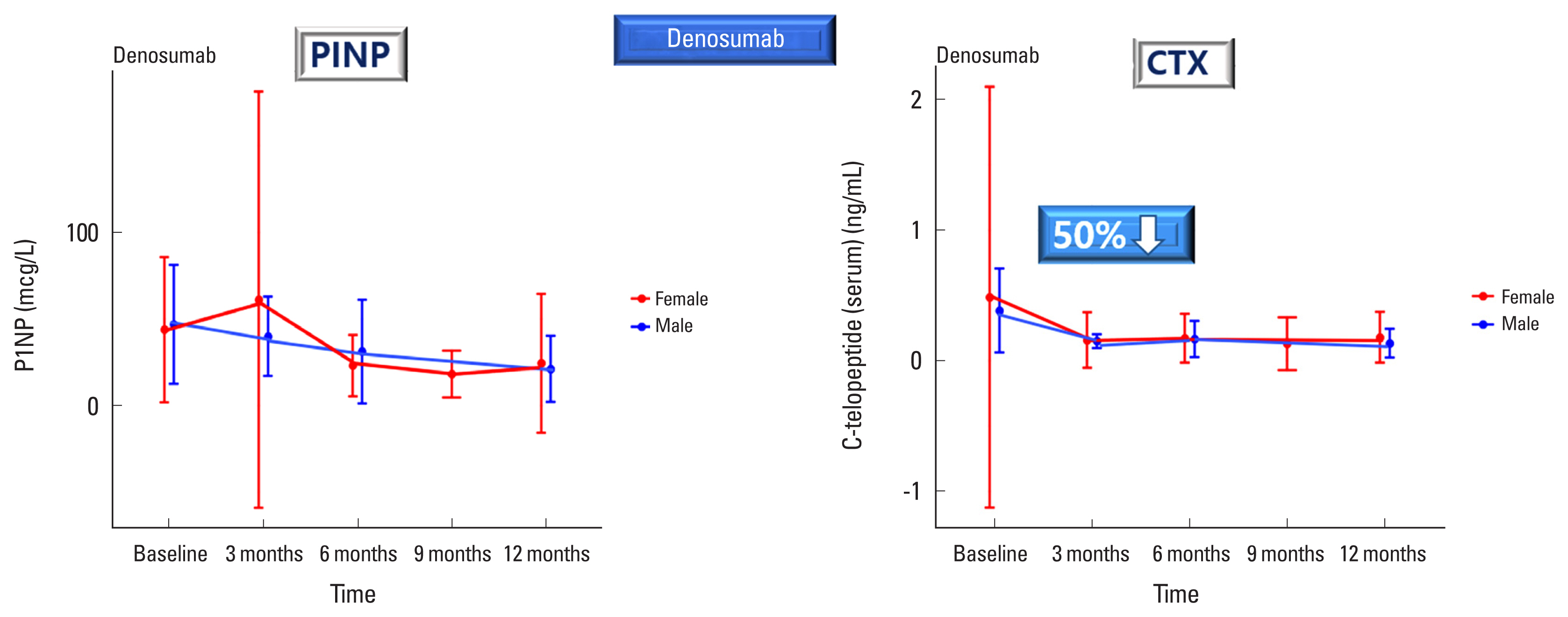

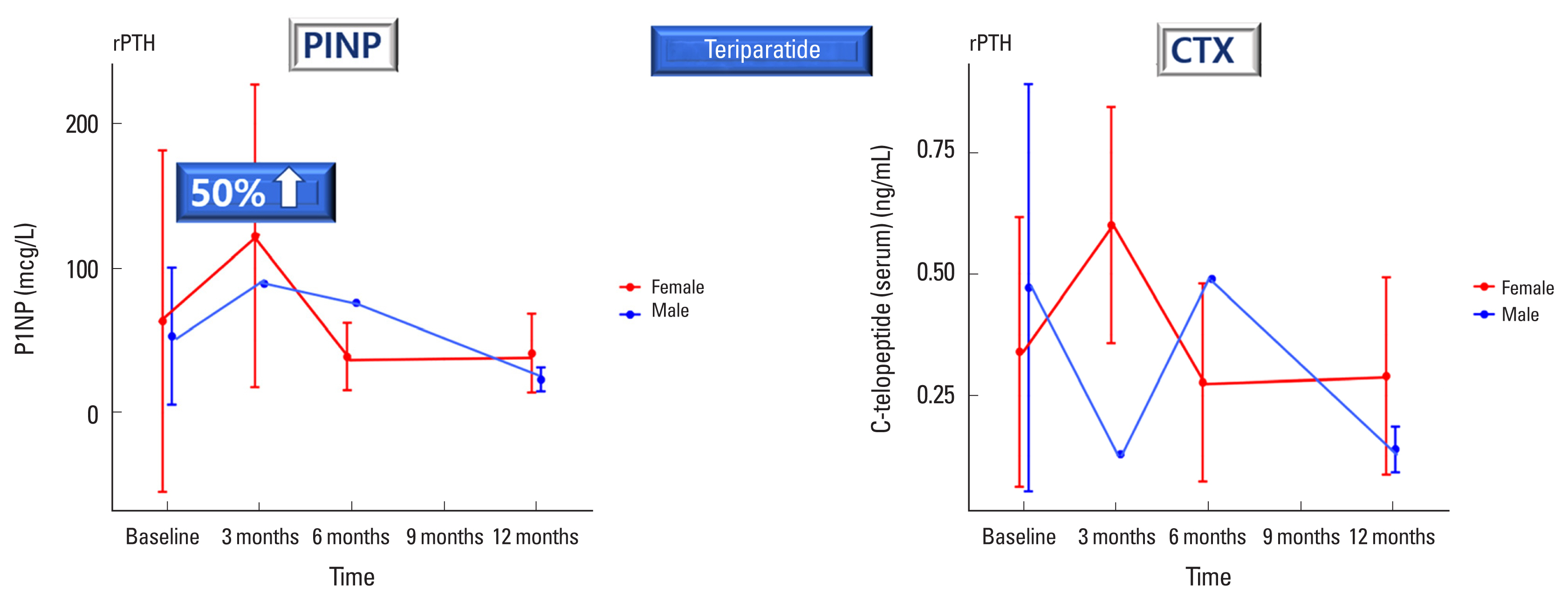

In addition, when teriparatide was treated in osteoporosis patients, P1NP increased after 3 months in both males and females, and a 50% increase was observed in females (P<0.05) (Fig. 1). Likewise, when treated with denosumab, CTX decreased after 3 months in both men and women, and it was reduced by 50% in women (P<0.05) (Fig. 2).

Plasma levels of propeptide of type I collagen (P1NP) and C-telopeptide (CTX) after teriparatide treatment in men and women with osteoporosis. rPTH, recombinant parathyroid hormone.

DISCUSSION

In the past decade, several BTMs have been developed to monitor bone metabolism.[7] P1NP, one of the most important BTMs, has been used to predict the rate of bone loss. It can be routinely monitored in osteoporosis patients for evaluation of treatment efficacy. In addition, reduction of P1NP level has been demonstrated as a marker for predicting bone fracture in many studies.[8–10] Before the development of an automated assay for P1NP, manual assay is the only method for measuring P1NP concentrations, thus limiting the clinical application of P1NP. However, high-throughput automated assays for P1NP have been introduced to clinical laboratories recently.[11] These assays could meet the increasing needs of P1NP measurement with short turn-around-time and improved performance compared to manual method.

The present study provided a reference range of BTMs according to the presence or absence of fracture or osteoporosis among Koreans. In particular, by measuring the BTMs of normal women over 50 years of age, we provided reference values that can represent bone status of post-menopausal women. In addition, BTMs values according to the presence or absence of osteoporosis were also provided, through which information on the reference range of BTMs according to bone health conditions was provided. The reference values presented in the present study show results quite similar to the P1NP reference standard values in other countries (Fig. 3).[3,4,12–15]

The reference values presented in the present study and other countries. P1NP, propeptide of type I collagen.

In the elderly over the age of 70, it is the time when bone loss accelerates due to bone resorption.[16] Therefore, checking the bone status of the elderly population is important to prevent osteoporosis and falls. It could be a standard for the evaluation of elderly’s bone status in the future by providing normal figures without fracture or both fracture and osteoporosis.

In addition, when teriparatide was treated in female osteoporosis participants, P1NP increased by 50% after 3 months, and when treated with denosumab, CTX decreased by 50% after 3 months. These results show that if bone status is quickly diagnosed with BTMs and drug treatment is performed, the progression of bone damage due to aging can be slowed down or restored.

Several limitations of our study should be considered. First, we did not take other hormonal markers into account. Therefore, we could not select post-menopausal women. Second, due to the limited sample size, we had to establish a reference interval in 10-year-old unit. Since we could not enroll enough older men and women, the reference range for more than 60-year-old subjects could not be specified. Third, menopausal status was not considered. Fourth, since real-world data were collected retrospectively nationwide, all conditions could not be controlled. However, it can be assumed that the university hospitals included in this study are institutions with good quality control for BTM measurement and that measurement or laboratory errors were relatively low. Fifth, as a limitation of the retrospective study design, it was not possible to investigate the reasons such as whether BTM collected under the age of 60 was a secondary risk, whether it was a non-reimbursed prescription, or whether it was conducted for research purposes during a clinical trial. Sixth, an X-ray review was not investigated to distinguish fractures such as major fractures or osteoporotic fractures in all institutions. Furthermore, as this study primarily focused on descriptive statistical data, there were variations in data collection methods, periods, and other factors across all centers, making it challenging to directly compare statistical significance.

Nevertheless, this present study demonstrated the excellent performance of total P1NP immunoassay. These results could contribute to the appropriate assessment of bone turnover status in the Korean population. It also provides P1NP levels in the Korean population for comparison studies with other populations in the future.

Notes

Funding

This study was conducted with support from the Roche Diagnostic (Mannheim, Germany).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chung-Ang University Hospital, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Yonsei University Health System, Kyung Hee University Healthcare System, Pusan National University Hospital, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, and Inha University Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from participants.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.