|

|

| jbm > Volume 29(2); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

A rapid increase in bone turnover and bone loss has been observed in response to the discontinuation of denosumab. It led to an acute increase in the fracture risk, similar to that observed in the untreated patients. We aimed to investigate the effect of denosumab on osteoclast (OC) precursor cells compared to that of zoledronate.

Methods

The study compared the effects of denosumab (60 mg/24-week) and zoledronate (5 mg/48-week) over 48 weeks in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. From patients’ peripheral mononuclear cells, CD14+/CD11b+/vitronectin receptor (VNR)- and CD14+/CD11b+/VNR+ cells were isolated using fluorescent-activated cell sorting, representing early and late OC precursors, respectively. The primary endpoint was the changes in OC precursors after 48 weeks of treatment.

Results

Among the 23 patients, 11 were assigned to the denosumab group and 12 to the zoledronate group (mean age, 69 years). After 48 weeks, the changes in OC precursors were similar between and within the groups. Serum C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen levels were inversely correlated with OC precursor levels after denosumab treatment (r=−0.72, P<0.001). Lumbar spine, femur neck, and total hip bone mineral density (BMD) increased in both groups. Lumbar spine BMD increased more significantly in the denosumab group than in the zoledronate group.

Denosumab, a widely used antiresorptive drug, is a monoclonal antibody against the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL). It is a potent agent that has been proven to increase bone mineral density (BMD) and decrease fracture risk at both vertebral and nonvertebral sites.[1,2] However, a phenomenon commonly described as the “rebound phenomenon”, an acute increase in bone turnover and bone loss, has been observed upon discontinuation of denosumab.[3,4] The profound bone loss caused by this phenomenon leads to increased fracture risks, especially multiple vertebral fractures, similar to that observed in untreated patients.[4] Therefore, subsequent antiresorptive treatment after denosumab discontinuation is recommended to prevent a rapid increase in bone turnover.[5,6]

However, studies focusing on the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are limited. Upregulation of bone resorption and formation markers are observed within 3 months after discontinuation, which correlates with the period of acute BMD decrease.[6,7] Moreover, these bone turnover markers are persistently elevated for up to 2 years.[8] The denosumab-induced increase of the osteoclast (OC) precursor pool leading to rapid upregulation of bone resorption has been suggested as a mechanism in a few reports, but the evidence is limited.[9,10] However, the report by Fontalis et al. [10] was submitted as an abstract for a conference and has not been published yet. Therefore, detailed information is absent, making interpretation difficult. However, another study has suggested that osteomorphs may contribute to rapid bone loss after denosumab discontinuation, in a mechanism where mature OCs change their shapes to become actively resorbing OCs without changing the OC pool.[11] On the other hand, there were few studies reported that OC precursors were decreased after bisphosphonate treatment that they may inhibit OC differentiation.[12,13] Therefore, we designed the study to compare the effect between denosumab and bisphosphonate treatment.

Understanding the rebound mechanism requires clinical evidence as to whether OC precursor cell population increased or remained unchanged during denosumab treatment. Therefore, in this prospective open-label trial, we aimed to investigate the effect of denosumab on OC precursor cell pool and compared it to zoledronate using flow cytometry analysis.

The study was an open-label, 12-month, double-arm, prospective study in which 23 postmenopausal women received either denosumab (60 mg subcutaneously at weeks 0 and 24; N=11) or zoledronate (intravenous; 5 mg yearly at week 0; N=12). Patients were recruited from February 2018 to February 2020 at the Seoul National University Hospital. The enrolled participants were ambulatory postmenopausal women aged >50 years who were at a high risk of fracture. Patients at increased risk of fracture were defined as those who met one or more of the following criteria: (1) BMD T-score ≤−2.5, at the lumbar spine, total hip, or femur neck; and (2) ≥1 history of fragility fracture. Patients were excluded if they had prior use of intravenous bisphosphonates, oral bisphosphonates, denosumab, teriparatide, or glucocorticoids within 6 months, or use of estrogens or selective estrogen receptor modulators within 3 months at the time of enrollment. Patients with conditions that can influence bone metabolism were excluded, such as hyperparathyroidism; vitamin D deficiency; history of malignancy; history of significant cardiopulmonary, liver, or renal disease; history of severe psychiatric disease; or excessive alcohol intake. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB no. 1709-033-886).

As there was no clinical study to report the effect of denosumab on OC precursors, sample number calculation was based on a previous study of the effect of bisphosphonate on OC precursors.[3] Assuming the type 1 error as 0.05 and the power as 0.8, as the mean change of OC precursor cells during the treatment was −1.5±1.5%, the required number of subjects is 10 per group. Therefore 12 patients per group were required for enrollment, considering the dropout rate of 20%.

Standing height and weight of patients without shoes and in light clothing were measured by a trained nurse. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m2). Menopausal age, smoking status, and the fracture history were determined based on electronic health records and the questionnaire. Data was recorded by a trained nurse. Serum creatinine levels were measured using an AutoAnalyzer (TBA-200 FR NEO; Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan). The plasma 25-hydroxy-vitamin D (25[OH]D) level was measured using a radioimmunoassay (DiaSorin Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA) with an inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) of 11.1% and an intra-assay CV of 8.8%. Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels were measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay with a DXI-800 analyzer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA). The concentration of C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX) was determined using a chemiluminescent immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Serum parathyroid hormone levels were measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay with a Cobas e411 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics).

BMD (g/cm2) at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip was measured at baseline and 48 weeks after treatments using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (Lunar Prodigy; GE Medical Systems, Madison, WI, USA) and analyzed using Encore Software version 11.0, according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The average CVs for the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip BMD were 1.22%, 1.97%, and 1.30%, respectively. The L1-4 value was chosen for the analysis of lumbar spine BMD. The vertebrae with a compression fracture, obvious deformity, or severe sclerotic change were excluded from the analyses (e.g., L2-4 were included in the analyses if a compression fracture at L1).

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from patients receiving denosumab or zoledronic acid. PBMCs (5×105) were diluted in 100 μL fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer and stained with 1:100 dilutions of the following antibodies: CD14-phycoerythrin (product number 557154; BD PharmingenTM, San Diego, CA, USA), CD11b-allophycocyanin (product number 553312; BD PharmingenTM), vitronectin receptor (VNR)-fluorescein (product number 11-0519-42; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, lnc., Waltham, MA, USA), and 10 μg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) solution (product number 62248; Thermo Fisher Scientific, lnc.) for 20 min at room temperature. Finally, the cells were washed, resuspended in FACS Buffer (product number 07905; Thermo Fisher Scientific, lnc.), and analyzed using a BD LSRFortessa™ device (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) with BD FACSDiva™ (BD Biosciences) software.

Live monocytes were first selected based on the DAPI-negative population and forward (FSC-A) and side scatter (SSC-A) analysis. Monocytes were further gated based on CD14 expression. Changes in OC population after denosumab or zoledronic acid treatment were compared based on CD14+/CD11b+ expression. CD14+/CD11b+/VNR− and CD14+/CD11b+/VNR+ cells represent early and late OC precursors, respectively.

Normally distributed data are presented as mean±standard deviation, non-normally distributed data are reported as median (interquartile range), and categorical data are reported as number (%). The variables between the groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Within groups, variables at baseline and at 4, 24, and 48 weeks were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Correlation analysis was performed using Pearson’s correlation analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant at P value less than 0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA) and R version 3.4.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and graphs were presented using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

A total of 28 postmenopausal women who satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria agreed to participate in the study. Among them, 5 patients from the denosumab group withdrew their consent. Two patients withdrew before the initiation of the study and 2 dropped out because they could not visit the hospital at week 4. One patient refused to visit and blood samples could not be obtained at the last visit. The final study cohort consisted of 11 and 12 patients in the denosumab and zoledronate groups, respectively.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. Age, BMI, and history of fracture status were similar between the groups. Additionally, BMD at the lumbar spine, femur neck, and total hip and biochemical characteristics, such as 25(OH)D and bone turnover markers, were comparable between the groups.

As described in Table 2, within each treatment group, OC precursor cell populations did not significantly change during treatment. In all patients, the OC precursor cell population decreased by 30% after 48 weeks of treatment, while weeks 4 and 24 did not show a significant change from the baseline.

Between denosumab and zoledronate groups, the changes in the OC precursor cell population were similar. At baseline and after 4, 24, and 48 weeks, the OC precursor cell population did not differ significantly between the groups. Changes from baseline after 4, 24, and 48 weeks were also similar in both groups.

Changes in early and late OC precursor populations were measured (Supplementary Table 1, 2). Early OC precursors were decreased after 48 weeks of treatment in all patients. Early and late OC precursor changes were similar between treatment groups at baseline and 4, 24, and 48 weeks after treatment.

BMD was measured at baseline and after 48 weeks. Lumbar spine BMD significantly increased after 48 weeks in the denosumab group compared to that in the zoledronate group (lumbar spine BMD, 0.796±0.087 and 0.750±0.056 mg/cm2, P=0.033; % change of the lumbar spine BMD, 9.62 ±6.97% and 1.35±6.44%, P=0.013, respectively) (Fig. 1A). Femur neck and total hip BMD increased in both groups during the treatment, but the percentage change from baseline did not differ between the groups at week 48 (femur neck BMD, 0.684±0.069, 0.676±0.053 mg/cm2, P=0.763; % change of the femur neck BMD, 3.61±2.51%, 0.64±4.05%, P=0.055; total hip BMD, 0.796±0.087, 0.750±0.056 mg/cm2, P=0.183; % change of the total hip BMD, 2.42±2.59%, −0.26±4.36%, P=0.099, respectively) (Fig. 1B, C).

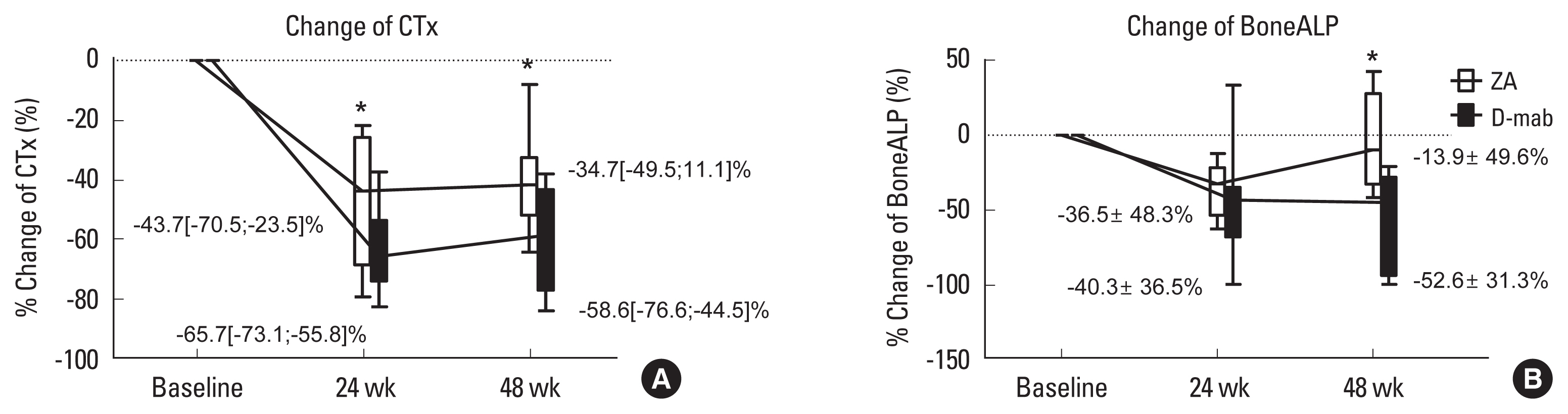

Bone turnover markers were measured at baseline and after 24 and 48 weeks. CTX levels were significantly reduced after 24 and 48 weeks compared with baseline in both groups (Fig. 2A). CTX levels after 24 and 48 weeks were lower in the denosumab group than in the zoledronate group (24 weeks, 0.105 [0.080; 0.128] and 0.183 [0.102; 0.205] ng/mL, P=0.034; 48 weeks, 0.117 [0.091; 0.166] and 0.235 [0.175; 0.314] ng/mL, P=0.008, respectively). In addition, bone alkaline phosphatase levels were significantly decreased after 24 weeks in both groups and at 48 weeks, bone ALP levels were significantly lower in the denosumab group than in the zoledronate group (week 24, 6.760 [6.370; 8.430], 8.520 [7.705; 10.775], P=0.114; week 48, 6.759±1.025, 11.962 ±2.368; P<0.001, respectively) (Fig. 2B).

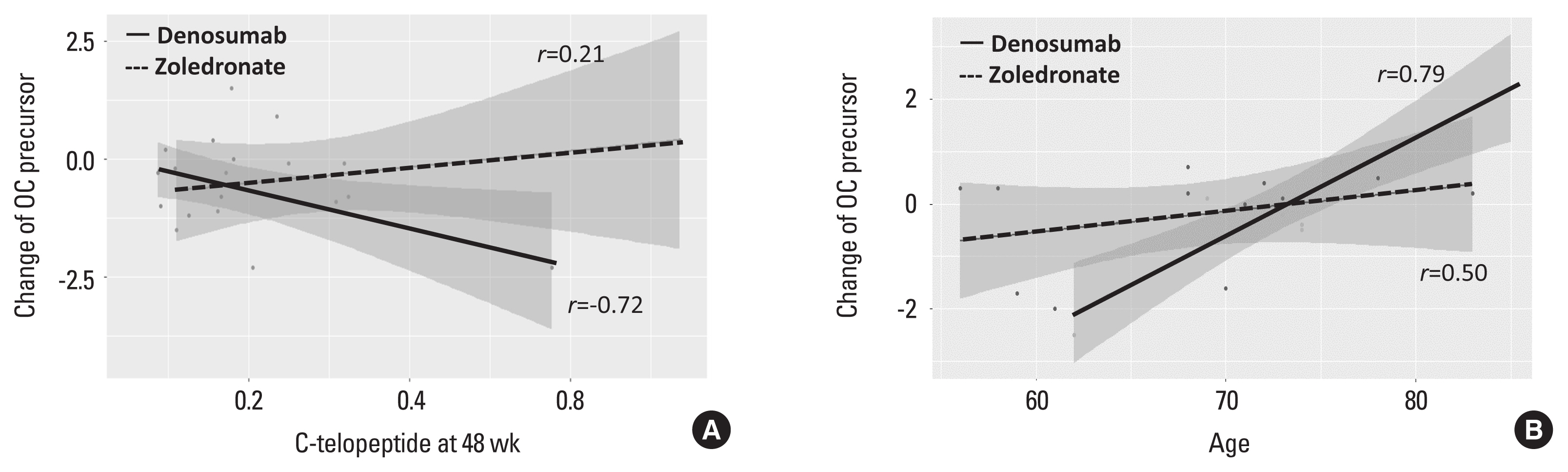

In the denosumab group, patients with lower CTX levels at 48 weeks had increased OC precursors at 24 and 48 weeks after treatment (Table 3, Fig. 3A). However, bone formation markers did not correlate with changes in OC precursors in either the zoledronate or denosumab groups. Patient age was positively associated with an increased % change of OC precursors at 24 and 48 weeks after denosumab treatment (Fig. 3B). In addition, in the zoledronate group, changes in OC at both 24 and 48 weeks did not correlate with clinical parameters such as age or bone turnover markers.

This prospective open-label trial compared the effects of denosumab and zoledronate on OC precursors. There were no significant changes in OC precursors, both early and late, between the denosumab and zoledronate groups. In addition, although were no significant changes with denosumab and zoledronate treatments, OC precursors in the 23 patients were reduced after 48 weeks of antiresorptive treatment. Patients who had older age or had more suppressed bone resorption status were likely to have increased OC precursor cells after treatment with denosumab.

Several studies have hypothesized that increased OC precursors during denosumab treatment may play a role in the rapid surge in bone resorption after discontinuation.[9,10] However, clinical studies have shown little evidence to support the hypothesis.[9,10] An abstract reported that OC precursors (CD14+/CD11b+) were more abundant after denosumab treatment than bisphosphonate treatment.[10] However, the interpretation requires caution because it was preliminary data presented as an abstract for a conference without detailed information. In addition, only follow-up results were presented without a baseline, so changes in OC precursors could not be assessed. Another study was based on data from 2 children who experienced rebound-associated hypercalcemia after denosumab treatment discontinuation.[9] Among them, an increase in circulating OC precursors was observed in one patient, based on CD16− monocytes. This study has limitations in that it only reported one case. Furthermore, CD16− monocytes cannot directly reflect OC precursors, including the CD14+/CD11b+ population as a subset. Therefore, clinical evidence is insufficient to support this hypothesis.

However, it has been recently hypothesized that changes in the form of mature OC, not the OC precursor pool, may contribute to the rebound phenomenon after reversible RANKL inhibition.[11] Since OCs express the RANK receptor, and the interaction between RANKL and RANK leads to OC differentiation,[14] it was estimated that blocking RANKL would increase OC precursors by blocking OC differentiation. However, there is no clear evidence that direct RANK inhibition increases the OC precursor population. In a recent in vivo study, intravital imaging showed that upon RANKL antibody treatment, mature OCs undergo cell fission to form osteomorphs, rather than accumulating OC precursors.[11] The rapid fusion of accumulated osteomorphs to actively resorb OCs after drug withdrawal may partly explain the rebound phenomenon.[11] As osteomorphs are not detected as CD14+/CD11b+ cells, the OC precursor population may not significantly contribute to the rebound phenomenon. In another in vitro study, denosumab or osteoprotegerin treatment did not increase OC precursor cells but decreased differentiated OCs compared to placebo.[15] Therefore, the inhibition of RANK signaling may not significantly affect the proportion of OC precursor populations among monocytes.

In addition, the OC precursor population did not change during the zoledronate treatment in this study. Bisphosphonates have been hypothesized to act on OC precursors and inhibit OC differentiation.[12,13] Some studies have investigated the effect of bisphosphonate treatment on the reduction of OC precursors.[16-19] Consistent with our results, there was no reduction in OC precursor levels during zoledronate treatment.[16] Although in vitro assays showed that zoledronate inhibited circulating OC precursors, OC precursors measured in human sera did not exhibit a significant reduction after 18 months of zoledronate treatment.[16] However, our findings differ from recent alendronate, risedronate, and ibandronate studies, which revealed a decrease in OC precursors (CD14+/CD11b+ cells).[17-19] In addition, direct sampling of the bone marrow revealed decreased osteoclastogenesis during alendronate treatment.[13] As in the previous zoledronate study, our negative results may be due to the relatively small sample size; the variations in circulating OC precursor levels between individuals could limit the sensitivity of the study.[16] It is also possible that the interval of bisphosphonate exposure may have influenced the results. Previous studies using bisphosphonates other than zoledronate administered them more frequently and were likely to induce higher circulating levels of the drug, which may have influenced OC precursors.[17-19] Therefore, although further studies with a larger sample size are needed, our data do not support the hypothesis that zoledronate reduces the OC precursor population.

In this study, old age and suppressed CTX levels were associated with increased OC precursor levels during denosumab treatment. Age and menopausal status have been reported to be positively correlated with the pool of OC precursors and differentiation in vivo and in vitro.[20-22] A previous study demonstrated an increase in CD14+ OC precursors during aging, leading to more aggressive bone resorption through alterations in DNA methylation and CathepsinK activation.[20] In agreement with previous studies, our results revealed an increase in OC precursors in older patients. It has also been reported that a more extended treatment duration of denosumab, reflected as more suppressed CTX, was associated with a more prominent bone loss after withdrawal.[23,24] Therefore, as shown in our association analysis, it is possible that those who had more suppressed CTX could be associated with the increased OC precursor during the denosumab treatment.

Detecting OC precursors in human blood has been a challenge, but a method has been established using flow cytometry.[25] CD14+ monocytes are a heterogeneous cell population from which macrophages originate.[26] In a previous report, human OC cells expressed the monocyte/macrophage markers CD14 and CD11b in the early osteoclastogenesis phase and lost their expression when they became functionally mature.[25,27] In addition, the selection of CD14+ monocytes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells enhanced osteoclastic bone resorption by over 2-fold compared to that in the unfractionated control.[25] CD14 and CD11b have also been used in other reports to represent OC precursors,[17-19] as our study. In addition, VNR is a typical OC phenotype that represents mature OCs.[28] OCs expressing VNR form F-actin rings and resorb the bone. “Actin rings” are OC-specific structures involved in anchoring OCs to the mineralized bone matrix prior to initiation of bone resorption.[29,30] Therefore, OC precursors with VNR expression are naturally low in number but may represent a relatively late phase OC precursors.[28]

This study has some notable strengths. This is the first prospective study to compare changes in OC precursors between denosumab and zoledronate treatments. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using fresh samples within 6 hr of collection. This study is clinically meaningful as it is the first to report the correlation between an increase in OC precursors and clinical parameters during denosumab treatment, such as age and suppressed bone turnover status. In addition, we measured OC precursors at multiple time points, such as 4, 24, and 48 weeks, to take a closer look at changes in OC precursors during the treatments. In addition to CD14 and CD11b, we measured VNR markers to assess early and late forms of OC precursors. Detailed measurements of the OC precursor population enhanced our understanding of the mechanism.

However, this study has some limitations. The required number of study participants was calculated based on previous studies investigating the effect of bisphosphonates on OC precursors. However, the number of patients enrolled in this study may be relatively insufficient to accurately observe the difference between groups. In addition, although flow cytometry analysis used fresh samples within 6 hr whenever possible, the timing of the analysis may have affected the results. In addition, it would be helpful to measure OC precursors more frequently to observe the trend, for instance, 2 to 3 months after injection, which may reflect the maximally suppressed bone turnover state.

In conclusion, our study is the first prospective study comparing the effect of denosumab and zoledronate on changes in the OC precursor pool. No significant difference in the OC precursor pool was observed between denosumab and zoledronate groups, suggesting that the OC precursor pool may not be significantly affected by RANKL inhibition. However, old age and suppressed bone turnover state were associated with an increased OC precursor pool in denosumab treatment, implying that more caution is needed in some populations after discontinuation. Further studies with a larger number of patients and extended observations are required.

DECLARATIONS

Fig. 1

Change of bone mineral density (BMD) during 48 weeks of denosumab and zoledronate treatment. Analysis were done using Student’s t-test in analyzing between groups, and paired t-test in analyzing within groups. *Represents P<0.05 between groups.

Fig. 2

Change of bone turnover markers during 48 weeks of denosumab and zoledronate treatment. Analysis were done using Student’s t-test in analyzing between groups, and from Wilcoxon signed-rank test in analyzing within groups. *Represents P<0.05 between groups.

Fig. 3

Correlation between change of osteoclast (OC) precursors and clinical parameters, such as (A) C-telopeptide at 48 weeks and (B) age. Pearson’s correlation analyses were done. Presented values are correlation coefficient of r.

Table 1

Baseline clinical characteristics of participants

| Denosumab (N=11) | Zoledronate (N=12) | P-valuea) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 73.0±6.3 | 67.1±8.2 | 0.069 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.1±3.8 | 22.7±3.5 | 0.727 |

| Menopausal age | 50.6±2.5 | 48.8±5.8 | 0.329 |

| Ever smoker | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.217 |

| History of fracture | 4 (36.4%) | 2 (16.7%) | 0.371 |

| Lumbar spine BMD (g/cm2) | 0.725±0.057 | 0.740±0.083 | 0.646 |

| Femur neck BMD (g/cm2) | 0.661±0.066 | 0.678±0.056 | 0.507 |

| Total hip BMD (g/cm2) | 0.703±0.067 | 0.727±0.056 | 0.372 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.71±0.09 | 0.70±0.11 | 0.991 |

| 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 33.7±12.6 | 36.1±20.6 | 0.739 |

| Bone ALP (μg/L) | 11.8±2.4 | 12.4±3.9 | 0.690 |

| CTX (ng/mL) | 0.40±0.25 | 0.41±0.22 | 0.907 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 38.0±24.3 | 32.7±14.5 | 0.595 |

Table 2

Comparison of changes of osteoclast precursors

| Denosumab (N=11) | Zoledronate (N=12) | Total (N=23) | P-valuea) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1.50 (1.35-1.85) | 1.15 (0.85-2.55) | 1.40 (1.0-2.0) | 0.422 |

|

|

||||

| Week 4 | 1.50 (0.95-2.75) | 1.50 (0.75-2.05) | 1.50 (0.85-2.15) | 0.372 |

| Change from baseline | 0.30 (−0.30-0.85) | −0.10 (−0.85-0.10) | −0.10 (−0.55-0.55) | 0.228 |

| %Change from baseline | 19.05 (−22.40-33.75) | −12.50 (−28.89-5.26) | −9.09 (−28.89-25.26) | 0.372 |

| P-value (baseline - week 4)b) | 0.367 | 0.250 | 0.621 | |

|

|

||||

| Week 24 | 1.40 (1.0-1.50) | 1.30 (1.15-2.10) | 1.30 (1.0-2.0) | 0.915 |

| Change from baseline | −0.10 (−0.40-0.40) | 0.20 (−0.80-0.35) | 0.10 (−0.40-0.40) | 0.803 |

| %Change from baseline | −6.25 (−28.57-20.51) | 20.0 (−18.09-40.97) | 15.79 (−28.57-36.36) | 0.545 |

| P-value (baseline - week 24)b) | 0.784 | 0.419 | 0.462 | |

|

|

||||

| Week 48 | 0.70 (0.40-1.50) | 0.75 (0.45-1.75) | 0.70 (0.40-1.70) | 0.669 |

| Change from baseline | −0.30 (−1.0-0) | −0.55 (−1.30-0.15) | −0.30 (−1.10-0) | 0.972 |

| %Change from baseline | −25.0 (−72.73-0) | −38.44 (−61.03-6.25) | −30.0 (−71.43-0) | 0.831 |

| P-value (week 0 - week 48)b) | 0.052 | 0.127 | 0.024 | |

Table 3

Correlation coefficient between change of osteoclast precursors and clinical parameters

| Baseline OC | Denosumab | Zoledronate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Change of OC (24 weeks) | Change of OC (48 weeks) | Change of OC (24 weeks) | Change of OC (48 weeks) | ||

| Age | −0.17 | 0.92a) | 0.79a) | 0.73 | 0.5 |

|

|

|||||

| Creatinine | −0.60 | 0.28 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

|

|

|||||

| 25(OH)D | −0.29 | 0.09 | −0.08 | 0.35 | −0.10 |

|

|

|||||

| Change of LS BMD | 0.09 | −0.17 | −0.44 | −0.05 | −0.31 |

|

|

|||||

| Change of FN BMD | −0.25 | −0.46 | −0.6 | −0.11 | −0.57 |

|

|

|||||

| Change of TH BMD | 0.45 | −0.63 | −0.71 | 0.04 | 0.44 |

|

|

|||||

| CTX at 24 weeks | 0.19 | −0.70a) | −0.79a) | −0.08 | 0.21 |

|

|

|||||

| BALP at 24 weeks | −0.39 | −0.62 | −0.36 | 0.29 | −0.26 |

|

|

|||||

| CTX at 48 weeks | 0.29 | −0.79a) | −0.72a) | 0.02 | 0.27 |

|

|

|||||

| BALP at 48 weeks | −0.23 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.45 |

REFERENCES

1. Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2009;361:756-65.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0809493

.

2. Bone HG, Wagman RB, Brandi ML, et al. 10 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:513-23.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(17)30138-9

.

3. Brown JP, Roux C, Törring O, et al. Discontinuation of denosumab and associated fracture incidence: analysis from the Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis Every 6 Months (FREEDOM) trial. J Bone Miner Res 2013;28:746-52.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.1808

.

4. Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, et al. Effects of denosumab treatment and discontinuation on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:972-80.

https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-1502

.

5. Tsourdi E, Langdahl B, Cohen-Solal M, et al. Discontinuation of denosumab therapy for osteoporosis: A systematic review and position statement by ECTS. Bone 2017;105:11-7.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2017.08.003

.

6. McClung MR, Wagman RB, Miller PD, et al. Observations following discontinuation of long-term denosumab therapy. Osteoporos Int 2017;28:1723-32.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-3919-1

.

7. Miller PD, Bolognese MA, Lewiecki EM, et al. Effect of denosumab on bone density and turnover in postmenopausal women with low bone mass after long-term continued, discontinued, and restarting of therapy: a randomized blinded phase 2 clinical trial. Bone 2008;43:222-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2008.04.007

.

8. Iranikhah M, Deas C, Murphy P, et al. Effects of denosumab after treatment discontinuation : A review of the literature. Consult Pharm 2018;33:142-51.

https://doi.org/10.4140/TCP.n.2018.142

.

9. Deodati A, Fintini D, Levtchenko E, et al. Mechanisms of acute hypercalcemia in pediatric patients following the interruption of Denosumab. J Endocrinol Invest 2022;45:159-66.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-021-01630-4

.

10. Fontalis A, Gossiel F, Schini M, et al. The effect of denosumab treatment on osteoclast precursor cells in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone Rep 2020;13:100457.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bonr.2020.100457

.

11. McDonald MM, Khoo WH, Ng PY, et al. Osteoclasts recycle via osteomorphs during RANKL-stimulated bone resorption. Cell 2021;184:1330-47e13.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.002

.

12. Cornish J, Bava U, Callon KE, et al. Bone-bound bisphosphonate inhibits growth of adjacent non-bone cells. Bone 2011;49:710-6.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2011.07.020

.

13. Eslami B, Zhou S, Van Eekeren I, et al. Reduced osteoclastogenesis and RANKL expression in marrow from women taking alendronate. Calcif Tissue Int 2011;88:272-80.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-011-9473-5

.

14. Takahashi N, Maeda K, Ishihara A, et al. Regulatory mechanism of osteoclastogenesis by RANKL and Wnt signals. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2011;16:21-30.

https://doi.org/10.2741/3673

.

15. Wada A, Tsuchiya M, Ozaki-Honda Y, et al. A new osteoclastogenesis pathway induced by cancer cells targeting osteoclast precursor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019;509:108-13.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.12.078

.

16. Dalbeth N, Pool B, Stewart A, et al. No reduction in circulating preosteoclasts 18 months after treatment with zoledronate: analysis from a randomized placebo controlled trial. Calcif Tissue Int 2013;92:1-5.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-012-9654-x

.

17. Gossiel F, Hoyle C, McCloskey EV, et al. The effect of bisphosphonate treatment on osteoclast precursor cells in postmenopausal osteoporosis: The TRIO study. Bone 2016;92:94-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2016.08.010

.

18. D’Amelio P, Grimaldi A, Cristofaro MA, et al. Alendronate reduces osteoclast precursors in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2010;21:1741-50.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1129-1

.

19. D’Amelio P, Grimaldi A, Di Bella S, et al. Risedronate reduces osteoclast precursors and cytokine production in postmenopausal osteoporotic women. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23:373-9.

https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.071031

.

20. Møller AMJ, Delaissé JM, Olesen JB, et al. Aging and menopause reprogram osteoclast precursors for aggressive bone resorption. Bone Res 2020;8:27.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41413-020-0102-7

.

21. Jevon M, Sabokbar A, Fujikawa Y, et al. Gender- and age-related differences in osteoclast formation from circulating precursors. J Endocrinol 2002;172:673-81.

https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.0.1720673

.

22. Chung PL, Zhou S, Eslami B, et al. Effect of age on regulation of human osteoclast differentiation. J Cell Biochem 2014;115:1412-9.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.24792

.

23. Popp AW, Varathan N, Buffat H, et al. Bone mineral density changes after 1 year of denosumab discontinuation in postmenopausal women with long-term denosumab treatment for osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 2018;103:50-4.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-018-0394-4

.

24. Gonzalez-Rodriguez E, Aubry-Rozier B, Stoll D, et al. Clinical features of 35 patients with 172 spontaneous vertebral fractures after denosumab discontinuation: a single center observational study. Quebéc, Canada: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; 2018. p.1010.

25. Massey HM, Flanagan AM. Human osteoclasts derive from CD14-positive monocytes. Br J Haematol 1999;106:167-70.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01491.x

.

26. Pickl WF, Majdic O, Kohl P, et al. Molecular and functional characteristics of dendritic cells generated from highly purified CD14+ peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol 1996;157:3850-9.

27. Athanasou NA, Quinn J. Immunophenotypic differences between osteoclasts and macrophage polykaryons: immunohistological distinction and implications for osteoclast ontogeny and function. J Clin Pathol 1990;43:997-1003.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.43.12.997

.

28. Lader CS, Scopes J, Horton MA, et al. Generation of human osteoclasts in stromal cell-free and stromal cell-rich cultures: differences in osteoclast CD11c/CD18 integrin expression. Br J Haematol 2001;112:430-7.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02437.x

.

29. Anderson DM, Maraskovsky E, Billingsley WL, et al. A homologue of the TNF receptor and its ligand enhance T-cell growth and dendritic-cell function. Nature 1997;390:175-9.

https://doi.org/10.1038/36593

.

30. Lakkakorpi PT, Väänänen HK. Kinetics of the osteoclast cytoskeleton during the resorption cycle in vitro. J Bone Miner Res 1991;6:817-26.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.5650060806

.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 2 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 3,008 View

- 102 Download

- ORCID iDs

-

Sung Hye Kong

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8791-0909Jung Hee Kim

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1932-0234Sang Wan Kim

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9561-9110Song-Hee Lee

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4208-261XSang-Kyu Ye

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6102-6413Chan Soo Shin

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5829-4465 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement1

Supplement1 Print

Print