|

|

| jbm > Volume 29(4); 2022 > Article |

|

This article has been corrected. See J Bone Metab. 2023 Feb 28; 30(1): 115.

Abstract

Background

Probiotics are live microorganisms that confer health benefits on the host. Many animal studies have shown that among the probiotics, lactobacilli exert favorable effects on bone metabolism. Herein, we report the results of a randomized controlled trial performed to investigate the effect of Lactobacillus fermentum (L. fermentum) SRK414 on bone health in postmenopausal women.

Methods

The bone turnover markers (BTMs) and bone mineral density (BMD) in participants in the study group (N=27; mean age, 58.4±3.4 years) and control group (N=26; mean age, 59.5±3.4 years) were compared during a 6-month trial. BTMs were measured at pretrial, 3 months post-trial, and 6 months post-trial, while BMD was measured at pre-trial and 6 months post-trial. Changes in the gut microorganisms were also evaluated.

Results

Femur neck BMD showed a significant increase at 6 months post-trial in the study group (P=0.030) but not in the control group. The control group showed a decrease in osteocalcin (OC) levels (P=0.028), whereas the levels in the study group were maintained during the trial period. The change in L. fermentum concentration was significantly correlated with that in OC levels (r=0.386, P= 0.047) in the study group at 3 months post-trial.

Conclusions

Probiotic (L. fermentum SRK414) supplementation was found to maintain OC levels and increase femur neck BMD during a 6-month trial in postmenopausal women. Further studies with a larger number of participants and a longer study period are required to increase the utility of probiotics as an alternative to osteoporosis medication.

Osteoporosis is a chronic progressive bone disease characterized by decreased bone mass and quality that can lead to fragility fractures.[1] Postmenopausal osteoporosis is one of the most common forms of this condition. Hormonal deficiency, a drop in the level of estrogen, causes an imbalance between bone formation and resorption.[2] There are medications for treating osteoporosis. Despite the beneficial effects of these drugs on bone metabolism, their use is hindered by problematic side effects, including abnormal reactions in organs susceptible to estrogen, gastrointestinal trouble, atypical fractures, and injection site pain.[3]

Vitamin D and calcium are widely used as alternatives to prescribed drugs. However, studies have reported that calcium supplementation causes gastrointestinal symptoms and renal stones, and paradoxically, vitamin D might increase the risk of falls and fractures.[4-7] Therefore, alternative supplements are required.

Probiotics have recently come into the spotlight because they have favorable effects on bone metabolism. The Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization define probiotics as live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.[8] Although the exact mechanism of action of probiotics remains unclear, several studies have suggested that beneficial bacteria not only modify the composition of the metabolic activity of the gut microbiota but also modulate immunity at local and systemic levels.[9,10] Probiotic modulation of the gut microbiota can lead to modulation of gut serotonin causing bone formation by increasing calcium absorption and decreasing bone resorption.[11]

Promising results have been reported in animal studies in which probiotics were administered to affect bone metabolism.[12] However, inconsistent outcomes in human studies have hindered the use of probiotics to increase bone mineral density (BMD) by balancing bone metabolism. Appropriate selection of probiotic microorganisms is needed to cause the intended effects in the human body. Lee CS and, Kim SH from Korea University showed the anti-inflammatory and anti-osteoporotic potential of Lactobacillus fermentum (L. fermentum) SRK414 in an animal study. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the effects of L. fermentum SRK414 on bone health after 6 months of administration in postmenopausal women. We hypothesize that L. fermentum SRK414 would increase the level of bone turnover markers (BTMs) and possibly increase BMD as well.

This prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of our hospital (IRB no. B1904-532-004). This study was conducted from August 2019 to June 2020. Informed consent was obtained from all participants following a detailed explanation. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) older than 55 years; (2) postmenopausal women defined as not having had menstruation for more than 12 months from natural cause; (3) all of the T-scores were higher than −2.5, including femur neck, femur total, and lumbar spine; (4) those not on osteoporosis medication. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) postmenopausal women with pathological gynecologic or endocrinologic causes; (2) those who were already taking osteoporosis medication; (3) steroid use or any other medication that could affect bone metabolism; (4) those with gastrointestinal disease, renal disease, or other diseases that could affect bone metabolism; and (5) dropouts during follow-up.

Power analysis and sample size calculation were performed based on a study by Nilsson et al. 2018. N-terminal telopeptide level in the lactobacillus treatment study and control groups were used.; average in the study and control groups were 0.35 (standard deviation [SD], 3.8) and 4.6 (SD, 7.3), respectively. An α level of 0.05 and β error probability of 0.2 were used in the G*Power test. A sample size of 23 patients in each group was recommended; however, considering a follow-up loss rate of 40%, we collected 38 patients in each.

Participants were randomly assigned to 2 groups, i.e., the study group and control group, using a double-blinded process. Each participant was randomly assigned to a group using a randomization program. Those in the study group took a probiotics capsule (L. fermentum SRK414, 4.0×109 CFU),[13] and the control group took a placebo capsule (microcrystalline cellulose) twice a day before meals for 6 months. The placebo capsules had the same appearance and smell as the probiotics capsules. Both types of capsules weighed 280 mg and were refrigerated at 4 to 8°C. All participants were advised not to take any other osteoporosis drugs, and not to change their routine diet or physical activity.

Demographic data and intake adherence rates were recorded. All the participants were instructed to report any adverse side effects during capsule intakes. Only those patients with a compliance rate higher than 70% were included in the data analysis. All participants underwent dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA; GE Lunar, Madison, WI, USA) examination at pretrial and post-trial 6 months. DXA was performed by a single experienced examiner in the radiological department to reduce errors, and DXA reports were also performed by an experienced radiologist. BMD was measured at the femur neck, total femur, and total lumbar spine. BTMs were examined at pretrial, post-trial 3 months, and post-trial 6 months, including serum C-terminal telopeptide (CTX), osteocalcin (OC), bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, and estrogen. Each blood sample was obtained at 10 AM to exclude the possible effect of diurnal variation in BTMs. Gut microbiota concentration was measured using next-generation sequencing at pre-trial, post-trial 3 months, and post-trial 6 months.

Descriptive statistics including mean and SD, were conducted for all the datasets. Data normality was analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The study and control groups were compared using the t-test for continuous variables using both intention to treat (ITT) and per protocol (PP) analysis. To identify the within-group difference between pre-trial and post-trial 3 months, and post-trial 6 months in the control and study groups, a repeated measures ANOVA test and paired t-test were adopted. The correlation between changes in BTMs and BMD was investigated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and statistical significance was set at P value of less than 0.05 (2-sided).

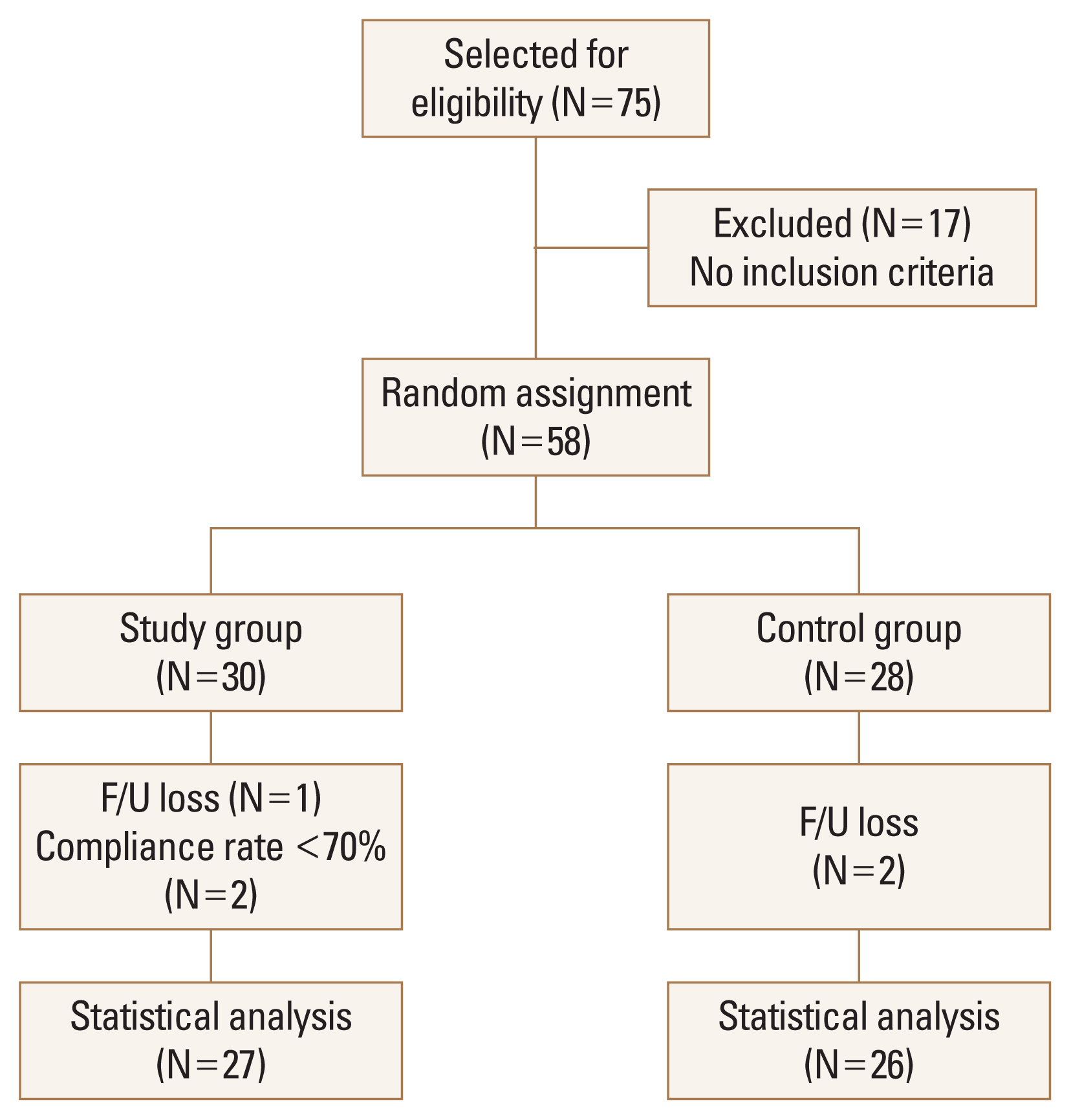

A total of 53 patients (27 in the study group and 26 in the control group) were included in the analysis. Out of 17 participants who were excluded, 3 participants were on steroid medication, 1 participant was on antibiotics treatment, 6 participants had gastrointestinal disease, 3 participants had gynecologic disease, and 4 participants had endocrinologic disease. Five dropouts occurred during the study. Some participants complained of gastrointestinal problems including constipation and fullness in the stomach. However, these symptoms were not severe and occurred in both the study and cpontrol groups (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of age, height, BMD, and BTMs were not significantly different between the study and control groups, except for body weight and body mass index (BMI) both in ITT and PP analysis (Table 1, 2).

Although BMD did not show a significant change at post-trial 6 months in the control group, femur neck BMD showed a significant increase at post-trial 6 months in the study group (P=0.030 in PP analysis P=0.043 in ITT analysis) (Table 3, 4). In the control group, OC significantly decreased during the 6-months trial period (P=0.028 both in ITT and PP analysis) while there was no significant change in CTX. In the study group, neither OC nor CTX showed any significant change over the 6-months study period (Table 5, 6).

No significant difference in BTM was observed between the study and control groups at post-trial 3 months. In addition, there were no significant differences in BTM or BMD at post-trial 6 months. The OC of the study group tended to be greater than that of the control group at post-trial 6 months but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.091 in PP analysis P=0.072 in ITT analysis) (Table 7, 8).

The L. fermentum concentration in the gut at post-trial 6 months differed between the study group (mean, 0.008257; SD, 0.040) and the control group (mean, 0.000017; SD, 0.000), but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.301). The change in L. fermentum concentration was significantly correlated with that of OC (r=0.386, P=0.047) at post-trial 3 months in the study group. However, no significant correlation was found between the change in L. fermentum and that in BMD or BTMs in the study group during the overall 6-months trial.

This double-blind randomized controlled trial evaluated the changes in BTMs and BMD after 6 months of probiotic administration in postmenopausal women. Most of the measurements did not significantly between the 2 groups. However, considering the small number of cases and short-term follow-up period, L. fermentum SRK414 was found to have a potentially beneficial effect on OC and BMD of the femur neck during the trial period.

A significant within-group increase in BMD of the femur neck was observed in the study group, while no significant difference was observed in the control group after 6 months of the administration. However, there was no significant between-group difference in the pre- and post-trial BMDs. Considering the short time period, and the fact that an increase in BMD was found only in the femur neck, we are unable to conclude that the femur neck BMD increased after drug administration. However, considering the spontaneous loss of 1% to 2% BMD in postmenopausal women, the BMD results of this study could be meaningful.[14] Furthermore, femur neck fractures could be more morbid than osteoporotic spine fractures, as the former frequently require surgical management.[15]

In previous animal studies, significant changes in BMD have been observed in the probiotics treatment group.[12,16] However, previous human studies have reported inconsistent effects of probiotics on BMD in the lumbar spine and hip. Jafarnejad et al. [17] showed no significant change in BMD after supplementation with probiotics whereas Lambert et al. [18] reported a beneficial effect on BMDs of the lumbar spine and femur neck. Another study revealed increased BMD of the lumbar spine and decreased BMD of the femur neck.[19] Our study is partially in agreement with previous studies, as only the femur neck BMD in the study group showed a significant within-group increase. These unpredictable results are attributed to the diversity of ethnic groups, sample size, characteristics of normal gut flora, constituents, and administration of probiotic strains or doses. Furthermore, most of the studies, including ours, were performed within 12 months, which might be too short to evaluate the change in BMD because probiotics are expected to have less efficacy than osteoporosis medications.

Contrary to previous studies that showed a significant decrease in CTX with probiotic administration, our study showed no significant change in CTX in both the control or study groups. However, compared to the decrease in OC levels in the control group, OC levels were maintained in the study group.[17,18,20] Furthermore, a significant correlation between the changed concentration of L. fermentum SRK414 and OC was observed at 3 months post-trial. In most cases, bone formation and resorption markers are coupled and change in the same direction. This finding could imply that L. fermentum SRK414 enhances bone formation more than resorption via other complicated mechanisms. OC is produced by osteoblast and osteocyte cells during bone formation.[21] OC is currently in the spotlight showing its capacity beyond bone metabolism in organs like myofibrillar fiber as well as muscle mass.[20] OC regulates bone quality by aligning biological apatite parallel to collagen fibrils, which is important for bone strength to load the direction of the long bones.[22] Further study is needed to determine the mechanism of OC. Additionally, the relationship between the effect of L. fermentum SRK414 on OC and increased femur neck BMD needs further study.

Although the mechanism of action between bone metabolism and probiotics has not yet been elucidated, animal studies have suggested that probiotic bacterial species can regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin [IL]-6, IL-17, and receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand) affecting osteoclast recruitment and activation in estrogen deficiency setting.[23-26] Other studies have reported that gut microbiota can mediate the gastrointestinal absorption of bone-related nutrients and stimulate the production of intestinally derived estrogens.[27,28] It is also supported by another study reporting that the probiotic effect on BMD was dependent on the postmenopausal period.[19] However, the maintenance of bone formation markers (OC) by probiotics shown in our study requires further investigation.

Osteoporosis is a common consequence of aging, and osteoporotic fractures can lead to substantial morbidity, mortality, and economic burden.[29-31] Although there are many effective pharmacological agents that could prevent osteoporotic fractures, low adherence and persistence are problematic, with less than 50% of the prescribed individuals on medication for one year.[32,33] Non-adherence is associated with an increased risk of fracture and higher medical costs.[33,34] In this context, probiotic agents are considered promising alternatives to pharmacological agents, and the results of this study could be promising. Our study showed a satisfactory compliance rate (Fig. 1) and benefits in BTMs and the femur neck with a low dose of L. fermentum SRK414 (4.5×109 CFU) compared to other probiotic studies (usually over 1.0×1010 CFU). Further studies testing different doses of probiotics would help determine optimal dose for bone health.

This study has several limitations. First, the short-term follow-up period limits the generalizability of the study results. Second, there was a significant difference in BMI between the control group and the study group. This could have also affected the results of the study. Third, only one bacterial composition with a single dose was used in this study. Various doses of multiple species of probiotics would provide more information for choosing the most effective probiotics for bone health. Fourth, the condition of the normal gut flora, nutrition intake, and activities could affect the action of probiotics on bone metabolism. However, these possible confounding factors could not be controlled in this study.

This study has the following strengths. First, although there have been other human trials, there has not been a study on probiotics in South Korea. This is the first randomized control study on probiotics in South Korea. Race and nationality could be contributing factors to the mechanism and effect of probiotics on humans. Second, with the introduction of a supplement, safety is more important than efficacy. The fact that no major adverse events were recorded throughout the study shows the safety of L. fermentum probiotics on South Koreans. Third, we selected women with postmenopausal osteoporosis from natural causes which were not on osteoporosis medication. Postmenopausal osteoporosis is one of the most common causes of osteoporosis; thus, demonstrating the effects of probiotics on the participants is significant. Fourth, we directly measured the gut microbiota concentration of L. fermentum and evaluated the relationship between concentration, BMD, and BTM variables. Therefore, we were able to rule out other biases and observe the direct effect of probiotic concentration on bone metabolism. The clinical relevance of this study is that the results showed the safety and beneficial effect of probiotics on South Koreans.

In conclusion, probiotic (L. fermentum SRK414) supplementation maintained OC and femur neck BMD without any serious side effects during a 6-months trial in postmenopausal women. Further studies with a larger number of participants and a longer study period are required to increase the utility of probiotics as an alternative agent to osteoporosis medication.

DECLARATIONS

Fig. 1

Flow chart showing the selection of participants included in the final analysis. F/U, follow-up.

Table 1

Comparison of baseline characteristics between the study and control groups (per protocol)

Table 2

Comparison of baseline characteristics between the study and control groups (intention to treat)

Table 3

Changes in bone mineral density during the 6-month follow-up (per protocol)

| Control group (N=26) | Study group (N=27) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Pretrial | 6 months | P-valuea) | Pretrial | 6 months | P-valuea) | |

| Femur neck | 0.685±0.09 | 0.685±0.08 | 0.954 | 0.688±0.11 | 0.717±0.15 | 0.030 |

|

|

||||||

| Femur total | 0.817±0.11 | 0.811±0.10 | 0.347 | 0.841±0.12 | 0.831±0.12 | 0.146 |

|

|

||||||

| L-spine total | 0.876±0.15 | 0.878±0.15 | 0.592 | 0.900±0.10 | 0.891±0.11 | 0.055 |

Table 4

Changes in bone mineral density during the 6-month follow-up (intention to treat)

| Control group (N=26) | Study group (N=29) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Pretrial | 6 months | P-valuea) | Pretrial | 6 months | P-valuea) | |

| Femur neck | 0.685±0.09 | 0.685±0.08 | 0.954 | 0.691±0.11 | 0.716±0.15 | 0.043 |

|

|

||||||

| Femur total | 0.817±0.11 | 0.811±0.10 | 0.347 | 0.846±0.11 | 0.836±0.12 | 0.130 |

|

|

||||||

| L-spine total | 0.876±0.15 | 0.878±0.15 | 0.592 | 0.896±0.10 | 0.887±0.10 | 0.051 |

Table 5

Changes of bone turnover marker during the 6-month follow-up in each group (per protocol)

| Control group (N=26) | Study group (N=27) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Pretrial | Post-trial 3 months | Post-trial 6 months | P-valuea) | Pretrial | Post-trial 3 months | Post-trial 6 months | P-valuea) | |

| OC (ng/mL) | 21.50±6.55 | 21.64±6.88 | 18.01±5.85 | 0.028 | 21.72±8.06 | 21.83±9.87 | 21.06±6.97 | 0.497 |

|

|

||||||||

| CTX (ng/mL) | 0.57±0.16 | 0.56±0.14 | 0.54±0.16 | 0.615 | 0.57±0.22 | 0.58±0.22 | 0.58±0.24 | 0.587 |

Table 6

Changes of bone turnover marker during the 6-month follow-up in each group (intention to treat)

| Control group (N=26) | Study group (N=29) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Pretrial | Post-trial 3 months | Post-trial 6 months | P-valuea) | Pretrial | Post-trial 3 months | Post-trial 6 months | P-valuea) | |

| OC (ng/mL) | 21.50±6.55 | 21.64±6.88 | 18.01±5.85 | 0.028 | 22.17±8.01 | 21.89±9.51 | 21.23±6.97 | 0.318 |

|

|

||||||||

| CTX (ng/mL) | 0.57±0.16 | 0.56±0.14 | 0.54±0.16 | 0.615 | 0.59±0.22 | 0.59±0.21 | 0.58±0.23 | 0.644 |

Table 7

Comparison of BMD and bone turnover marker between the study and control groups during follow-up (per protocol)

Table 8

Comparison of BMD and bone turnover marker between the study and control groups during follow-up (intention to treat)

REFERENCES

1. Raisz LG. Pathogenesis of osteoporosis: concepts, conflicts, and prospects. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3318-25.

https://doi.org/10.1172/jci27071.

2. Pacifici R. Estrogen deficiency, T cells and bone loss. Cell Immunol 2008;252:68-80.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.06.008.

3. Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Boonen S, et al. Adverse reactions and drug-drug interactions in the management of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 2011;89:91-104.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-011-9499-8.

4. Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:1815-22.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.594.

5. O’Brien PE. Failure to report financial disclosure information in a study of gastric banding in adolescent obesity. JAMA 2010;303:2357.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.693.

6. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Orav EJ, et al. Monthly high-dose vitamin D treatment for the prevention of functional decline: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:175-83.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7148.

7. Khaw KT, Stewart AW, Waayer D, et al. Effect of monthly high-dose vitamin D supplementation on falls and non-vertebral fractures: secondary and post-hoc outcomes from the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled ViDA trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:438-47.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(17)30103-1.

8. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, World Health Organization. Guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food: Report of a joint FAO/WHO working group on drafting guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food 2002 [cited by 2022 Jun 1]. Available from: https://4cau4jsaler1zglkq3wnmje1-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/probiotic_guidelines.pdf.

9. Bron PA, van Baarlen P, Kleerebezem M. Emerging molecular insights into the interaction between probiotics and the host intestinal mucosa. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011;10:66-78.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2690.

10. Ohlsson C, Sjögren K. Effects of the gut microbiota on bone mass. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015;26:69-74.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2014.11.004.

11. Rizzoli R, Biver E. Effects of fermented milk products on bone. Calcif Tissue Int 2018;102:489-500.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-017-0317-9.

12. McCabe LR, Irwin R, Schaefer L, et al. Probiotic use decreases intestinal inflammation and increases bone density in healthy male but not female mice. J Cell Physiol 2013;228:1793-8.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.24340.

13. Lee CS, Kim SH. Anti-inflammatory and anti-osteoporotic potential of Lactobacillus plantarum A41 and L. fermentum SRK414 as probiotics. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2020;12:623-34.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-019-09577-y.

14. Johnston CC, Norton J, Khairi MR, et al. Heterogeneity of fracture syndromes in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1985;61:551-6.

https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-61-3-551.

15. Florschutz AV, Langford JR, Haidukewych GJ, et al. Femoral neck fractures: current management. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29:121-9.

https://doi.org/10.1097/bot.0000000000000291.

16. Kim JG, Lee E, Kim SH, et al. Effects of a Lactobacillus casei 393 fermented milk product on bone metabolism in ovariectomised rats. Int Dairy J 2009;19:690-5.

17. Jafarnejad S, Djafarian K, Fazeli MR, et al. Effects of a multispecies probiotic supplement on bone health in osteopenic postmenopausal women: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. J Am Coll Nutr 2017;36:497-506.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2017.1318724.

18. Lambert MNT, Thybo CB, Lykkeboe S, et al. Combined bioavailable isoflavones and probiotics improve bone status and estrogen metabolism in postmenopausal osteopenic women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:909-20.

https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.117.153353.

19. Jansson PA, Curiac D, Ahrén IL, et al. Probiotic treatment using a mix of three Lactobacillus strains for lumbar spine bone loss in postmenopausal women: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Rheumatol 2019;1:E154-E62.

20. Morato-Martínez M, López-Plaza B, Santurino C, et al. A dairy product to reconstitute enriched with bioactive nutrients stops bone loss in high-risk menopausal women without pharmacological treatment. Nutrients 2020;12.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082203.

21. Szulc P, Delmas PD. Biochemical markers of bone turnover: potential use in the investigation and management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2008;19:1683-704.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0660-9.

22. Komori T. Functions of osteocalcin in bone, pancreas, testis, and muscle. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207513.

23. DeSelm CJ, Takahata Y, Warren J, et al. IL-17 mediates estrogen-deficient osteoporosis in an Act1-dependent manner. J Cell Biochem 2012;113:2895-902.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.24165.

24. Kitaura H, Kimura K, Ishida M, et al. Immunological reaction in TNF-α-mediated osteoclast formation and bone resorption in vitro and in vivo. Clin Dev Immunol 2013;2013:181849.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/181849.

25. Humphrey MB, Nakamura MC. A comprehensive review of immunoreceptor regulation of osteoclasts. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2016;51:48-58.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-015-8521-8.

26. Ohlsson C, Engdahl C, Fåk F, et al. Probiotics protect mice from ovariectomy-induced cortical bone loss. PLoS One 2014;9:e92368.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092368.

27. Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, et al. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 1997;337:670-6.

https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199709043371003.

28. Chiang SS, Pan TM. Beneficial effects of phytoestrogens and their metabolites produced by intestinal microflora on bone health. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2013;97:1489-500.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-012-4675-y.

29. Ray NF, Chan JK, Thamer M, et al. Medical expenditures for the treatment of osteoporotic fractures in the United States in 1995: report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. J Bone Miner Res 1997;12:24-35.

https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.1.24.

30. Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, et al. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:465-75.

https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.061113.

31. Tarride JE, Burke N, Leslie WD, et al. Loss of health related quality of life following low-trauma fractures in the elderly. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:84.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0259-5.

32. Fatoye F, Smith P, Gebrye T, et al. Real-world persistence and adherence with oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027049.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027049.

33. Modi A, Tang J, Sen S, et al. Osteoporotic fracture rate among women with at least 1 year of adherence to osteoporosis treatment. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:767-77.

https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2015.1016606.

34. Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81:1013-22.

https://doi.org/10.4065/81.8.1013.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 2,888 View

- 184 Download

- ORCID iDs

-

Hee Soo Han

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8865-1718Jung Geul Kim

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5530-6056Yoon Hyo Choi

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2386-1594Kyoung Min Lee

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2372-7339Tae Hun Kwon

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9710-1400Sae Hun Kim

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0990-2268 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print