INTRODUCTION

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are used in a wide range of clinical settings and play a major role in the treatment of various inflammatory diseases.[

1] In the USA, an estimated 1.2% of the general population uses GCs chronically.[

2] For rheumatic diseases, GCs are one of the most frequently prescribed drugs, and a previous study using a large nationwide cohort in Korea reported that up to 83% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) were receiving or had received GC therapy.[

3]

Long-term GC use is associated with loss of bone density and deterioration of bone microstructure leading to increased fracture risk, primarily in the trabecular bones such as vertebrae.[

4,

5] Although the fracture risk increases with the dose and duration of GC use, the risk increases most rapidly within 3 to 6 months of initiation of oral GC therapy.[

6,

7] Therefore, early intervention strategies for GC-induced osteoporosis (GIOP) are critical for preventing fractures.[

4,

8]

Numerous guidelines for the management of GIOP patients have been published and updated by each country and academic society.[

9] Some guidelines did not differentiate GC users from the general population. They use the fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX) for fracture risk assessment, and it reflects GC use as a risk factor.[

10] On the other hand, some GIOP-specific guidelines have been developed separately from the guidelines for postmenopausal women, and these provide distinct threshold values.[

11]

The Korean GIOP guidelines were recently developed by adapting established guidelines from other countries, but intervention thresholds had not been fully investigated.[

12] Because it is important to grasp appropriate thresholds to prevent fractures during exposure to GCs, we systematically reviewed societal and national guidelines for GIOP and compared intervention thresholds in each guideline.

DISCUSSION

We reviewed recommendations with regard to intervention thresholds in both GIOP-specific guidelines and overall osteoporosis guidelines. Although recommendations are based on the rationale that the association of fracture risk with GCs is exposure-dependent, thresholds vary among the guidelines. The criteria for defining intervention thresholds were refined in accordance with the development of fracture risk assessment tools. Before the introduction of FRAX, intervention thresholds were based on the degree of GC exposure or BMD score. However, over time, the criteria for identifying patients who should receive preventive treatment has shifted towards country-specific FRAX values.

Previous epidemiological studies have demonstrated that the increased risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fracture is related to GC dose and exposure.[

4,

5,

8] Even doses as low as 2.5 or 7.5 mg of prednisone-equivalents per day can be associated with a 2.5-fold increase in vertebral fractures and 1.7-fold increase in hip fractures.[

4] The risk increases rapidly within 3 to 6 months after the start of GCs and is greater in patients exposed to higher doses continuously for a longer period.[

7,

8,

26] In accordance with these results, thresholds of 5 or 7.5 mg per day with a duration for 3 months or greater are consistently accepted in the most guidelines, and an initial clinical fracture risk assessment as soon as possible within 6 months of GC initiation is strongly recommended.[

11,

12]

The conventional BMD T-score of −2.5 is usually applied to the guidelines for postmenopausal osteoporosis treatment; however, some guidelines apply less stringent T-score values because the fracture risk is much higher in GIOP compared to that expected based on DXA values.[

27,

28] At similar BMD levels, the incidence of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women was considerably higher in GC users than nonusers.[

27] Moreover, in a meta-analysis of international cohorts, a direct relationship between BMD score and fracture risk was not verified in GIOP.[

28] GCs have adverse effects on trabecular bone microarchitecture independent of BMD and the changes in the bone quality that contribute to increased risk of fracture often do not translate into a decrease in BMD scores.[

29-

31] Although these findings provide the rationale for a T-score threshold different from that of postmenopausal osteoporosis, there is no established T-score threshold for bone-protective therapy in patients taking GCs. From the earlier guidelines, T-score thresholds of −1.0 or −1.5 were included as an independent criterion for intervention with pharmacological treatment.[

15,

32] Thereafter, the same values have been adopted by numerous guidelines.[

17,

19,

20,

25]

However, the higher BMD cut-off point is not an evidence-based threshold, but rather an accepted value considering the discrepancy between BMD data and fracture data in GC users. It is unclear whether (and to what degree) the less stringent BMD threshold predicts fracture risk in individuals using GCs, and whether it is cost-effective in terms of drug therapy. Therefore, a more comprehensive approach beyond the BMD which considers various clinical risk factors for fracture is particularly important in GIOP.[

33]

The recognition that consideration of independent risk factors and BMD together is more accurate in predicting fracture probability compared to BMD alone has led to the development of fracture risk tools that incorporate various clinical risk factors, including oral GCs.[

34,

35] Of these tools, FRAX is the most externally validated and widely used.[

36] Since its release in 2008,[

37] the use of FRAX combined with intervention thresholds has been recommended by many national and societal postmenopausal osteoporosis treatment guidelines.[

10,

18,

24,

25,

38] The ACR has also incorporated FRAX as an assessment tool for fracture risk in GIOP in its 2010 revised guidelines.[

39] Furthermore, in 2012, the joint Guideline Working Group of the IOF-ECTS suggested a fracture probability-based approach using FRAX in its framework for the development of guidelines for GIOP management.[

20]

The dose relationship between GC use over 3 months and fracture risk can be employed in the FRAX model, which allows the estimates to be adjusted depending on GC dose.[

40,

41] FRAX assumes an average dose of prednisone (2.5-7.5 mg/day or its equivalent) and adjustments according to doses have been proposed in several guidelines. In the 2017 NOGG guidelines, the average adjustment for postmenopausal women and men over 50 years of age is a factor of 0.8 for low-dose exposure and 1.15 for high-dose exposure for major osteoporotic fractures; these adjustment factors are 0.65 and 1.20, respectively, for hip fractures.[

10] However, since these adjustments may provide a limited estimate of the risk associated with very high-dose GC exposure, some guidelines additionally recommend pharmacological intervention in adults receiving very high-dose GCs, independent of BMD and FRAX values.[

11,

12,

25]

In spite of these adjustments to overcome the limitations of the conventional FRAX algorithm, FRAX makes no distinction between past and current GC use and lacks the ability to estimate fracture risk in premenopausal women and men under 40. In addition, its predictive value for identifying individuals at high risk of fracture has been primarily validated for hip fractures.[

42,

43] Considering these limitations, FRAX was not incorporated into the revised Japanese guidelines.[

21] In addition, like BMD values, FRAX also has a weakness with respect to its reproducibility in GIOP, because the performance of the FRAX algorithm was validated for the general population. Although RA, which requires GC therapy and is itself a risk factor for fracture independent of GIOP,[

44] is included as one of the dichotomous factors in the estimation of fracture risk, FRAX does not encompass disease activity and duration, which are significantly associated with increased fracture risk.[

45,

46] Thus, its application of the same thresholds derived from the general population to patients with GIOP, or to patients with a specific disease that is itself a cause of osteoporosis, may result in a risk of error.[

47]

Recently updated recommendations have suggested less stringent FRAX cut-off points than those for postmenopausal osteoporosis for determining when anti-osteoporosis intervention is in order.[

11,

12,

25] The 2017 ACR guidelines recommend pharmacological intervention in patients with a 10-year major osteoporotic fracture risk of greater than 10% or a 10-year hip fracture risk of greater than 1%. The thresholds of 10% and 1% are lower than the generally accepted thresholds of 20% and 3% for postmenopausal osteoporosis.[

38] The guideline developers made recommendations based on absolute fracture risk reduction with treatment in each stratum, classified according to the incidence of vertebral fractures over 5 years. However, fracture data is lacking in GIOP-specific clinical trials and population studies; therefore, most fracture data for these recommendations were extrapolated from general osteoporosis clinical trials.[

11] The 2017 NOGG guidelines suggest an age-dependent intervention threshold using FRAX, not a fixed-threshold. This approach is based on the rationale that if a woman with a prior fragility fracture is eligible for treatment, then, at any given age, a woman with the same fracture probability but in the absence of a previous fracture should also be eligible.[

48] Given the cost-effectiveness of this case-finding strategy in the UK, where provision for BMD testing is suboptimal, an age-dependent fracture probability determines the thresholds at which to intervene both for treatment and for BMD testing.[

48,

49] The same strategies are recommended for individuals taking GCs, with an additional independent threshold that patients exposed to greater than 7.5 mg of prednisone-equivalents per day are eligible for therapeutic intervention.[

10] However, fracture risk might be underestimated in patients who have been treated for a long time with a lower dose of GCs when the NOGG guidelines are applied. In addition, recommendations for intervention thresholds in younger GC users are rather limited.

The discrepancies between the 2 main guidelines on GIOP arise from diversity in local conditions, such as health care policies, cost of treatment, and accessibility to BMD, as well as different fracture probabilities across the countries. However, the majority of guidelines, especially using a fixed-FRAX probability, have adopted an identical threshold value as the USA, without their own health economic analysis.[

48] The paucity of data on GIOP-induced fractures makes it difficult to develop evidence-based guidelines in other countries as well, with a great variation in rigor scores among the guidelines.

In Korea, the 2018 guidelines for GIOP prevention and treatment contain the accepted thresholds of FRAX and BMD which were suggested by the ACR. Given the lack of domestic data, the working group decided to adapt previously published guidelines and presented the same intervention thresholds from the 2017 ACR guidelines.[

12] After its publication, the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service in Korea announced that pharmacological intervention for the prevention of fracture is available for prolonged GC users whose BMD T-score is −1.5 or less.[

50] To set the best target for intervention in patients taking GCs while considering cost-effectiveness, it is necessary to consider the benefits and limitations of FRAX and BMD, accessibility to BMD testing, and other clinical risk factors in the context of GIOP-induced fracture in order to set the appropriate thresholds.

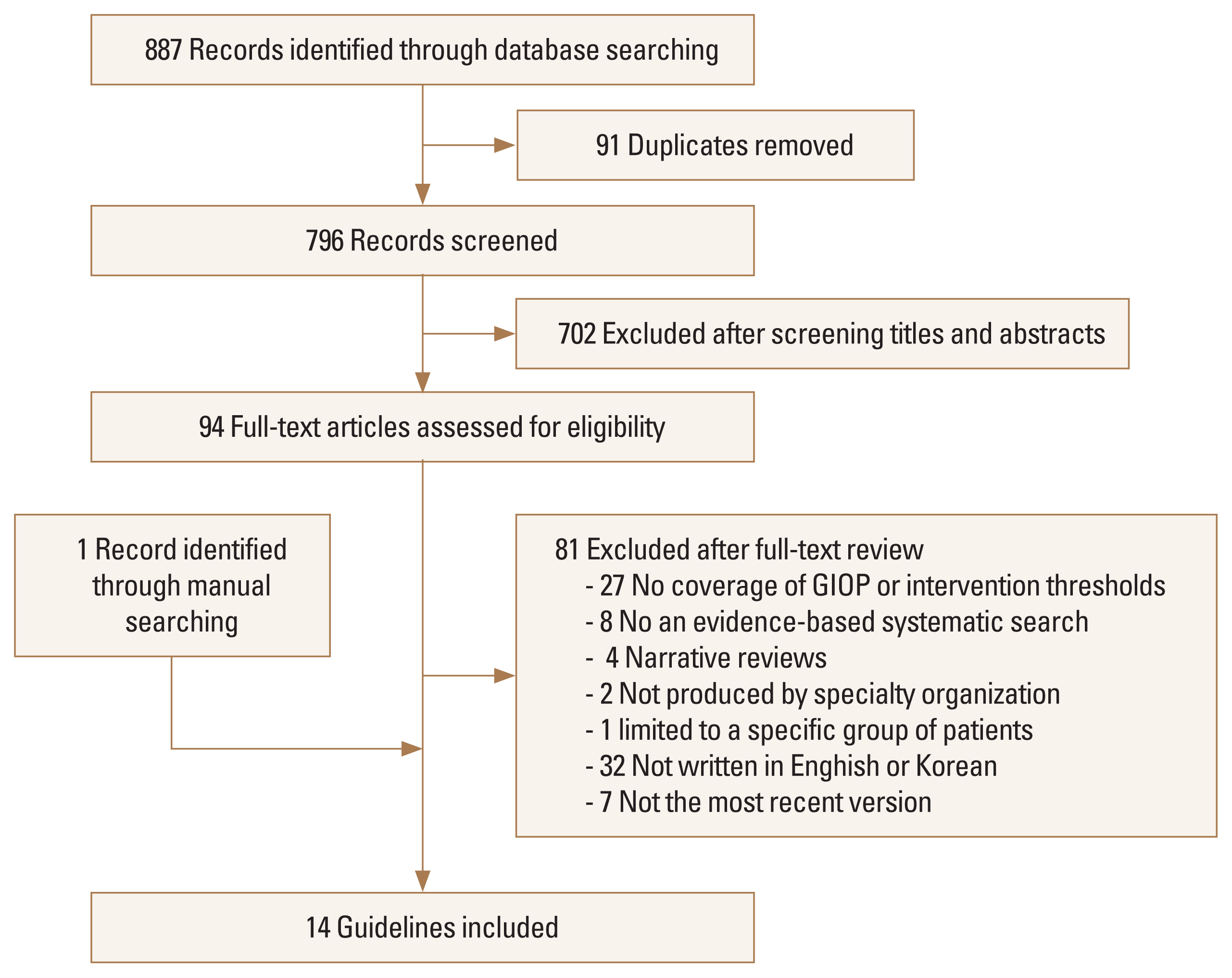

Despite a sensitive search strategy for eligible guidelines, explicit selection criteria for eligibility, and appraisal of the guidelines using the AGREE II instrument, several limitations could have biased our findings. First, only guidelines written in English were included, and guidelines written in other languages may have been overlooked. Second, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, which is a public resource of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and widely used for guideline searching, was not included in the search database because it was not available at the time of the literature search. Thus, we might have missed some eligible guidelines. Third, the quality of the evidence underpinning the recommendations was not investigated because the AGREE instrument evaluates the methodological rigor and transparency with which a guideline is developed and not the quality of its contents. Moreover, statements of the strengths and limitations of data in the guidelines were mainly concerned with anti-osteoporosis drugs. For this reason, a comprehensive investigation of previous studies supporting the recommendations was performed to identify the evidence underpinning the effectiveness of thresholds for therapeutic intervention in the current GIOP guidelines.

In conclusion, the results of our review showed that GIOP guidelines have proposed thresholds distinct from those of postmenopausal osteoporosis, given the natural history of bone loss caused by GCs. Since the introduction of FRAX, a FRAX-based approach has been incorporated into the criteria for defining intervention thresholds. However, high-quality data pertaining to these thresholds that can warrant intervention in GC-treated patients are still limited. Further studies assessing fracture as a primary outcome with established tools, such as FRAX and DXA, in chronic GC users could aid in setting tailored intervention thresholds in GIOP guidelines.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement1

Supplement1 Print

Print